The building in Würzburg that once “sheltered” the medieval Jewish tombstones was called “Landelektra” and was located opposite “St. Gertud Church” near the city center.

The demolition of this building commenced in the winter of 1987, quite rapidly, without consideration of the importance of the tombstones.

While tearing down the building, more and more Jewish tombstones were found. This was a stunning discovery for David Schuster, the former chairman of the Jewish community in Würzburg, and he was at a loss.

The Bavarian Ministry of Culture intervened after strong public protest and stopped the demolition of the building for several weeks. During that time it was possible to save more tombstones. Pictures of the remaining stones in the walls of the “Landelektra” could be taken and already visible fragments could be photographed “in situ” and it became possible to translate the Hebrew inscriptions that were already recovered.

The stones were of tremendous importance not only because the majority of the stones could be dated, but also because it was possible to newly rank the importance and the educational level of medieval Würzburg’s Judaism in the Jewish world more precisely.

After that short break, the demolition of the building continued. The construction company, however, agreed on storing and collecting Jewish tombstones on wooden palettes next to the construction site.

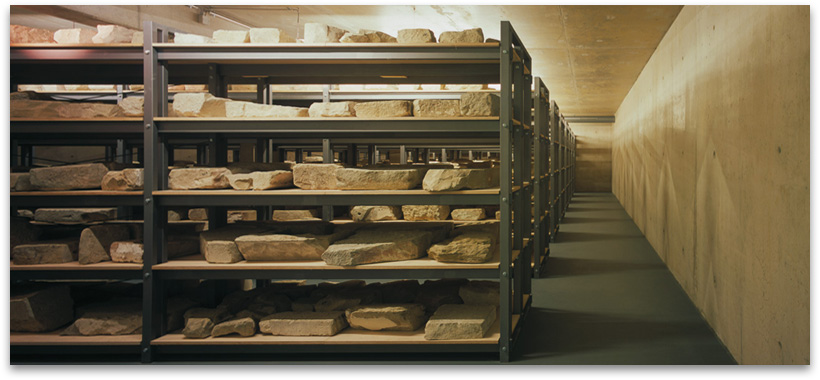

The majority of the stones were later temporarily taken to the Jewish cemetery in Werner-von Siemens-Straße in Würzburg. There the stones were covered with plastic. The minority of the stones was taken to Oberthür Vocational School over the winter.

It was in the summer of 1987 when the “Judensteine”, what they were called in those days, were transported to a location, where the scholastic and scientific research could be started through the help and mediation offered by the city of Würzburg, they were taken to a place called “Rotkreuzhof”. They were stored there for the next 19 years.

In the beginning, 175 male and female students from the Catholic Faculty of the University of Würzburg worked voluntarily for 4271 hours to register, clean, and photograph the stones. The University of Würzburg and the Bavarian Ministry of Culture supported this project financially.

The first decryption of all Hebrew inscription was supported by Rabbi Simcha Bamberger, the great-grandson of the “Würzburger Rav” who is presently the Jewish Gaon in Manchester/England. Since 1996, a scholar team paid by the German-Israeli foundation has been reading and studying the legends of the stones. Part of this project team was Dr. Schim’on Schwarzfuchs (Tel Aviv, Paris), Professor Dr. Rami Reiner (Be’er Schäv‘a), Dr. Edna Engel (National Library in Jerusalem) and Professor Dr. Dr. Karlheinz Müller (Würzburg)

The most difficult task was to put together the different pieces that were once broken into many fragments, to fit into the walls of the medieval Dominican monastery St. Marcus (later known as “Landelektra” ).

All data and inscription of the Jewish tombstones date back to the years 1147 and 1347. They are the testimony of almost exactly 250 years of Jewish history in Würzburg: from its beginning around the year 1100, to 1349, when the outbreak of the Black Death put an end to Jewish life, under the accusation of poisoning the wells.

Deutsch

Deutsch English

English Русский

Русский Español

Español Italiano

Italiano